Spot prices are the mechanism by which the energy market signals the needs of the power system to participants, investors, and consumers. So when we see something strange occurring in the behaviour of spot prices, it warrants attention. In this article we examine how spot prices are becoming more ‘noisy’ (ie, they are oscillating more frequently). We present analysis of spot price noise, some preliminary theories about what is causing it, and what the consequences may be.

What do we mean by noise?

First, we must define the concept of spot price noise. From a mathematical perspective, noise is the transient oscillation of a time series that is typically overlaid on top of some underlying trend. Note however that ‘noise’ is typically random, although it is not entirely without structure.

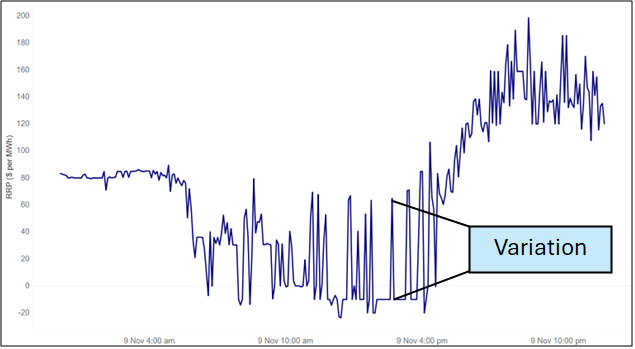

For our purposes, we use the mathematical concept of ‘variation’ as our proxy for noise – ie, the difference between any two consecutive intervals between the spot prices. For example, when spot prices for 4 intervals are $50, $100, $75, $20 then the variation outcomes are $50, -$25, -$55. Figure 1 illustrates the concept of variation on a recent day for NSW.

Figure 1 – Illustration of variation; NSW 9 November 2025

Given that we are not interested in scarcity events where prices signal underlying shortage of generation, we have capped all prices at $300 per MWh before calculating variation. We do not see these outcomes as noise, but rather an important signal in prices to reflect scarcity. In addition, when summing variation over time we will also use the concept of the absolute value of variation to capture both positive and negative movements, which might otherwise cancel each other out.

Variation has been rising

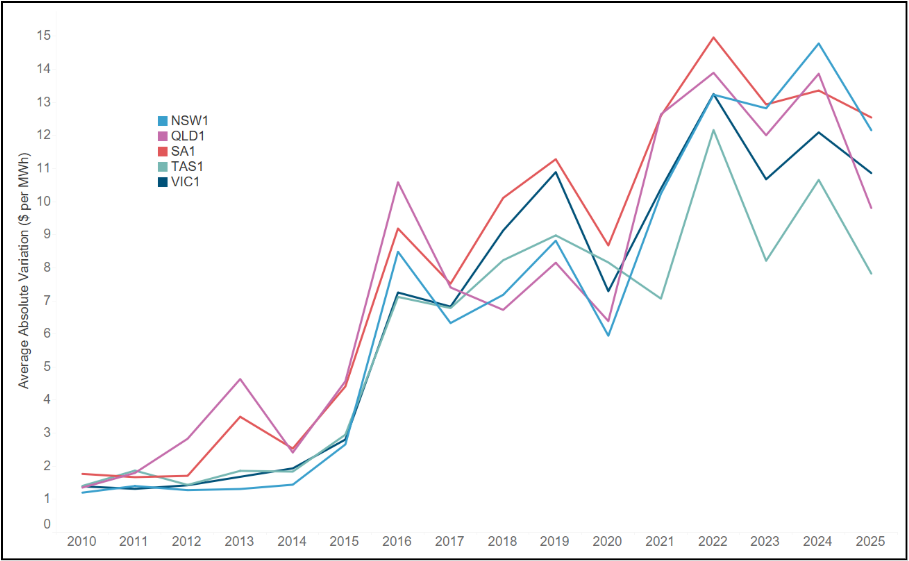

What has been happening to variation over the history of the NEM? Figure 2 shows the average absolute variation from 2010 to 2025 for each region of the NEM. The rise in variation is enormous. In 2010, the average difference between 2 dispatch intervals was around $1 per MWh across all regions; in 2025 that number exceeded $10 per MWh.

Figure 2 – Average absolute variation by NEM region, 2010 to 2025

What else do we know about variation?

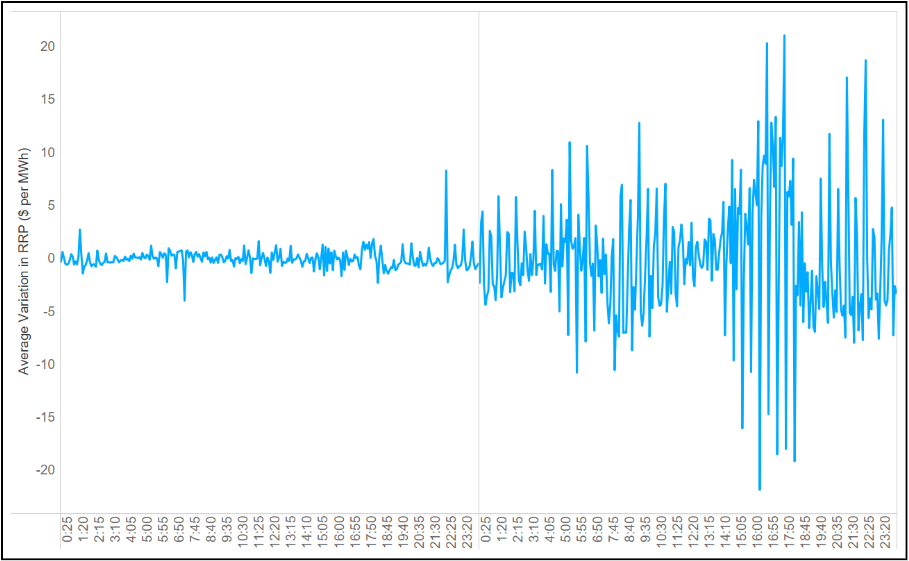

Figure 3 shows average variation by time of day for NSW in 2010 and 2025. Two observations:

- Variation has increased across the day, but it is greater at some times than others. This would be expected due to the presence of the duck curve, but there are also increases in variation during the middle of the day and overnight.

- There appears to be a periodicity to the average variation in 2025 – it exhibits spikes that seem to occur with a regular frequency.

Figure 3 – Average variation in NSW by time of day, 2010 versus 2025

It is this second feature that is of most interest. Why should there be any intraday structure to the average noise if it is indeed just caused by random perturbations in the supply and demand curves? Is there something causing the noise that means it is in fact partially deterministic rather than purely stochastic?

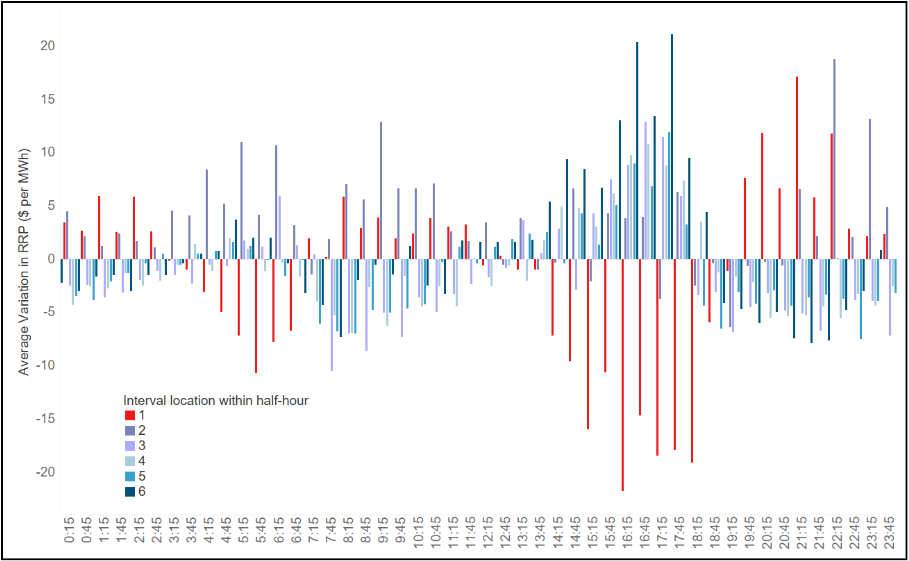

Figure 4 shows the average variation by time of day for NSW. To aid in the visualisation we have added colours to each observation based on where the dispatch interval occurs during the half-hour (ie, a number between 1 and 6).

Figure 4 – Average variation in NSW by time of day, Calendar Year 2025

The results are striking:

- The positive spikes in variation tend to occur in the last 5 minutes of the half hour (shown in dark blue).

- The negative spikes in variation tend to occur in the first 5 minutes of the half-hour (shown in red).

- There is a clear structure to the variation depending on the location within the half-hour.

This seems to suggest that the ‘noise’ we are seeing is, at least in part, being driven by something structural that depends on the temporal location within the half-hour.

Why is variation so structured?

With 5-minute settlement having been in effect for some time, the temporal structure of variation is surprising – why does it matter whether it is the first or last interval of the half-hour? There are only two possible overarching causes: demand or supply. We start with a look at supply.

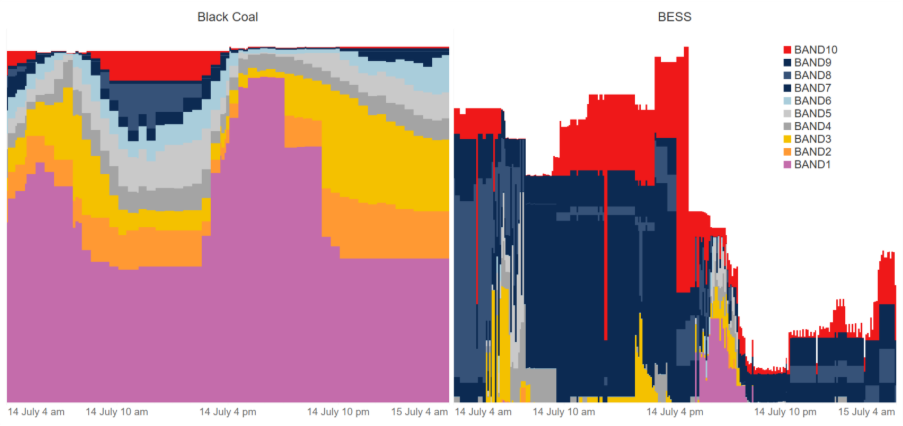

A simple analysis of bids in NSW reveals at least one possible reason for the structure. Figure 5 shows a recent sample of the aggregate final bid stacks for NSW Black coal on the left and NSW BESS on the right. Interestingly, the bid stack of NSW Black Coal is defined on a half-hourly basis, whereas BESS varies by 5-minute interval.

Figure 5 – Sample of bids for NSW black coal and NSW BESS

This would suggest that the supply curve is flat within the half-hour. We have analysed the bids for all thermal generators in the NEM, and a large proportion of them still supply bids on a half-hourly basis. Interestingly, Snowy’s bids are defined on a 5-minute interval basis.

Much more analysis would be required to pin down the exact relationship between noise and the supply-demand balance. But at this stage, we posit that an increased variability in both demand and VRE have led to increased variability in the exact point at which supply clears against demand. At the same time, bid structures have remained relatively lumpy and have not (with the exception of batteries and some hydro) adapted to the changing conditions. The root cause of the change in noise warrants deeper analysis, but the 30-minute structure of bids seems a good starting point.

What are the consequences of the increase, and possible vanishing, of noise?

Noise is a big part of the battery business case. Noise lifts the highest daily prices and drops the lowest daily prices. This increases the opportunity for arbitrage by batteries. Indeed, the challenge of obtaining a high ‘percentage-of-perfect’ outcome is driven by the increased presence of noise, which makes it harder to time charging and discharging to achieve an optimal outcome.

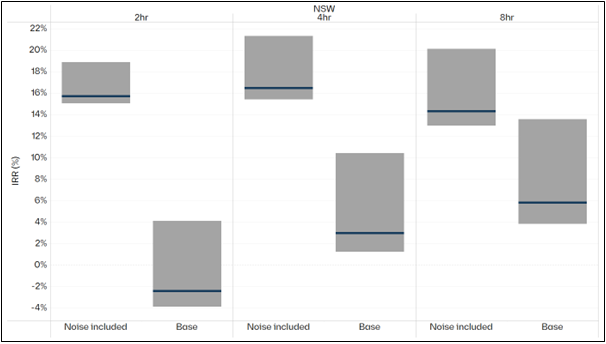

Figure 6 shows the range of returns to batteries in NSW of different durations with and without historical levels of noise being included in the modelling.

Figure 6 – IRR for indicative battery of different durations in NSW, noise versus base

The shorter the duration of the battery, the more dependent it is on noise. This makes sense because as duration increases, the spread of each full cycle must capture higher buy points and lower sell points.

Were noise to increase, the relative business case for shorter duration batteries would improve. Alternatively, were noise to decrease, the business case for shorter duration batteries would be more adversely affected than for longer durations.

It follows that investors and market participants need to have a better understanding of how the inclusion of noise affects their projects, and to stress-test their models to include different levels of noise.

Finally, we note that it is unclear whether noise is a feature or bug of the NEM. In particular, is it:

- a sophisticated signal provided by the energy only market, that we do not yet understand; or

- a pathological outcome of bidding behaviour that is making it harder to invest and make sensible decisions.

More to come from us on this in the coming months.